The Bees' Knees, Needs, and More

Local keepers reveal complex picture of hives, honey

It’s a glorious May afternoon, and I’m riding down I-94, the hum of the road eclipsed by a droning thrum all around me.

In the four-row van are a quarter million passengers, some loose flying around our heads and bouncing off the windows.

I’m riding shotgun next to Charlie Koenen, with a swarm of bees in the back: a spring shipment of 43 bee “packages” we picked up in Watertown, each bearing 5,000 bees and one queen. His company, Beepods, this day will make deliveries in Lake Mills, Walker’s Point, the East Side and Riverwest before finishing at the community apiary in St. Francis, where more will be picked up the following day.

Honeybees have always drawn my curiosity. I grew up seeing them on the many cranberry bogs around Tomah each spring. During the three-week window for pollination, the beds would fill with hundreds of thousands of bees traveling among a sea of pink blossoms. Stacks of white Langstroth hives (the most common type, which looks like a stack of boxes) would mark their homes, one to four per acre. Besides clover, cranberry was one of my early flavors of honey.

Making the Rounds

On Koenen’s delivery route our first stop in Lake Mills is right off the highway in a McDonald’s parking lot. We meet a father and two kids, and load four packages (screened box with 5,000 female workers, sugar water feed, queen in a sub-cage for protection) into the back of their pickup. After some questions about hive maintenance, Koenen describes to the dad a new mobile app allowing better hive monitoring, to keep bees healthy.

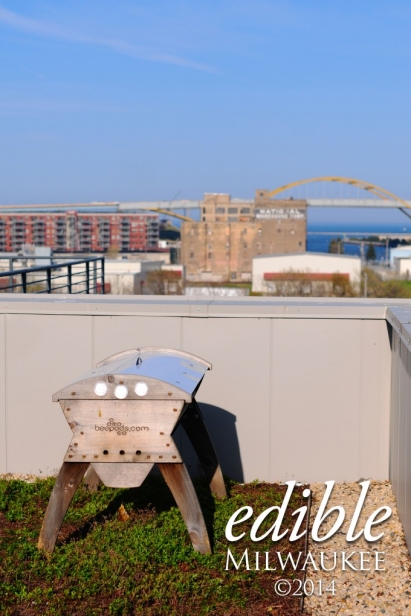

Our next drop-off with a spectacular view is Fix Development’s rooftop garden atop the Clock Shadow Building in Walker’s Point. This 3,000-square-foot green space overlooks Downtown, Jones Island and south towards Bay View. On this stop we were installing a package into a “Beepod,” a top bar hive designed by Keonen. This Beepod had some comb from the hive that didn’t “overwinter” (survive to the spring), which we left in to save the bees some energy and give them a jumpstart on their new home.

Top bar hives are horizontal rather that vertical, and Beepods use wood bars with a mid-vein on the underside that give bees a foundation from which to build downwards. Though Beepods encourage bees to build vertical comb via tailored “bee space,” they also allow bees to build without too much structure.

Koenen’s supplier, Lee Heine, is one of the largest national distributors of packaged bees, and is well respected in our area. His queens are bred in Hawaii and are introduced to daughters in California. Essentially, a package of bees is an artificial swarm. Commercial beekeepers are mimicking a natural process where a new queen is raised in the hive, and before she hatches the old queen and half the workers leave in a “swarm,” splitting the hive. After the brutal winter we just went through, Lee Heine’s business has been booming.

Back on the roof, with the Allen-Bradley Clock Tower as a backdrop, I arm myself with a feather and a marshmallow. As Koenen’s helpful assistant, I stand by as he removes the feeder can and the queen in her darling little cage. Carefully – Koenen will be stung several times this day – he pulls out the cork and replaces it with the mini marshmallow I hand him. It will eventually be eaten by the workers to slowly release the queen. He next tips and dumps out the 5,000 workers into the hive. I assist by taking a feather (preferred over a brush) and scooping and pushing clumps of misplaced bees in to join the others. Amazingly, they immediately start orienting themselves and cleaning their new, partially-furnished residence.

With evening closing in, and bees flying out the windows, our beemobile pulls up at our next drop-offs: two backyards of inspired urban homesteaders, eagerly awaiting their new extended family members. We install both packages, and by the end we are both answering questions and educating the new parents. By now, though, it’s getting late and cold, and the bees are done moving for the day.

Urban Apiary

From a moving van, my next stop for bees takes me to the shadows of Hwy 45. There, in the Firefly Ridge Community Garden Apiary, Linda Reynolds of the UW-Extension Urban Apiculture Institute has been keeping bees for the last seven years.

Throughout the year she teaches beekeeping classes, and was able to give me a crash course on the craft’s benefits and challenges. A master gardener and naturalist, Reynolds used to consider herself a purist when it came to the environment, choosing “native-only” options whenever possible. North America does have native bees, but the effectiveness and usefulness of the honeybee is what brought them from Europe. The past seven years have led to an “evolving respect for bees and their needs,” she said, with foraging plants, both native and non-native, critical to her principles. The plight of the bees is “in the forefront of how I think and what I do,” she says.

Bees have long inspired wonderment because of their industriousness. One worker bee can make up to one and a half teaspoons of honey in its brief lifetime of a few months. To make one pound of honey, bees needs to visit more than 2.6 million flowers and fly 15,000 miles, according to the Canadian Honey Council. I’m here at Linda’s to learn more about how bees and their colonies, which I come to see as “mini-cities,” operate.

A brown picket fence gives entrance to the apiary with a roaring highway above. Inside are two (out of six) active hives that overwintered and were bringing in the first pollen of the season, drawn primarily from surrounding dandelions and other wildflowers. In successive relays, worker bees pass each other in the cork-sized hole, legs laden with yellow saddlebags going in, empty legs flying out. This early-season nectar produces a pale yellow, smooth, crystallized honey.

Worker bees always surround the queen to service her; in order to collect honey in a Langstroth hive a “queen excluder” screen allows workers and male drones to pass through, leaving comb and honey stores to accumulate in comb boxes called “supers” above. This is why hives seem to grow as the season progresses. To collect pollen, keepers add screens that knock off the saddles, which collect on a bottom drawer, before bees pack the pollen away in comb for protein caches. Like honey, the flavor and appearance depends on the source, and covers the color spectrum from yellow to purple. A lesson Reynolds stresses to her students is bee products must be responsibly collected – too much will make them struggle and leave them ill prepared for winter.

Bees and their by-products have had many uses throughout history. In addition to wax for candles and honey for medicinal purposes, bee venom, propolis, pollen, and royal jelly have all found culinary and medicinal uses (e.g. stinger venom for arthritis).

Wild Bees

My final visit took me to a friend’s home. When I learned Denis Zalucha had been keeping bees in his backyard for the past 35 years, I realized I had access to a wealth of experience. What I discovered was a bee-human relationship that’s deep, balanced, and symbiotic. Further, Denis also exposed me to the wider variety of honey flavors and their pairings.

To my friend Denis, bees are “wild animals and they always will be.”

He supports this fundamental dynamic by interfering as little as possible, letting nature take her course. Finding a colony in spring that didn’t make it elicits grief and acceptance.

“One of the saddest things is to have a hive and know going into winter they do not have enough stores, are not going to make it, and there is nothing you can do about it,” Denis says.

In his backyard you will not find any chemicals, even those approved for “hive health.” He has witnessed an increase in diseases over the past 10 years. Reasons why are multifaceted, including different pathogens and parasites, but he has not seen CCD (see Sidebar: Plight of the Bees). His healthy hives he attributes to several factors, including his location outside Racine, removed from large agricultural fields using high levels of pesticides, and his careful approach to raising bees.

Sweet for the Sweets

As for the fruits of his labor, Denis takes delight in offering a honey tasting.

Honey’s taste and texture is dependent on the nectar the bees feed on and the moisture content in the environment – which is why spring honey is so cloudy and crystallized. “The many flavors of honey are like fine wine,” he says, and can range from honey locust and alfalfa to dandelion and buckwheat, all with varying colors and palate.

I try some orange blossom Denis serves, which has a deep amber hue and a hint of citrus, to compare next to buckwheat, which is dark and bold in taste – my senses take me immediately to molasses. The varieties of honey are boundless, and the food pairings to match? Infinite.

Local keepers say local, regional and national honey flavors can vary widely. In the supermarket, consumers buying honey from large, national brands may encounter homogenized honey blended from multiple suppliers that have moved their hives to take advantage of peak nectar, but in turn has lost its “local” character. This emerges more clearly from local sources because their bee husbandry relies more heavily on area pollen types, the timing of the collection, and the location and stability of the hives.

But how do our local beekeepers like their honey?

Doing a dish for guests, Denis said he would “use a light-flavored honey like basswood, tupelo or honey locust to go with a fruit like peaches, apples or pears.” His personal favorite? “I like my wildflower honey on homemade vanilla ice cream – honey thickens like maple syrup on snow and provides another feel to the mouth.”

Linda’s favorite honey is the first of the season – the product of a healthy hive and hard work done by the bees and their keeper. Besides savoring smooth honey straight out of the jar, she loves to sweeten her green tea.

Charlie, on the other hand, likes the taste that emerges from Beepods left stable, responding to subtle changes in local climate, nectar and pollen. What emerges are “isolated tastes” from what he calls “seasonal regional honey,” such as “South Side Milwaukee honey in spring, or Fond du Lac in fall.”

Kept in the right conditions honey almost never spoils. Crystallized honey can be placed in a jar in warm water and stirred until the crystals dissolve. Honey is sweeter and has more moisture than sugar, so in most recipes you can substitute one cup of sugar with ¼ cup honey. To bake with honey add ½ teaspoon of baking soda for every cup of honey, lower your oven temperature by 25 degrees, and add a few extra minutes.

(Due to possible bacteria infections please do not give honey to infants under one year of age.)

The Bees’ Needs

The main challenge bees face is us. Our food system has created a large-scale industry treating bees as a labor force whose productivity is to be maximized. Honey, like bees, is a product of the environment that mirrors its bounty and quality; we are seeing now what happens when bounty is increased at the expense of overall environmental health – including that of the bees.

What became clear from speaking with Koenen, Reynolds and Zalucha is that we have pushed bees too hard to keep up with the industrialization of our agriculture. Bees are sick because our current system exposes them to untold stresses of pesticides, diseases (from mass intersection of colonies in warmer states), and instability (from too much transport).

We all need an education. Our food supply would not exist without healthy bees and pollinators, and we need to see and act on their intrinsic, and not just their instrumental value. To Koenen, this requires a “paradigm shift” where people, acting from the bottom up, ultimately keep bees not just for their honey.

To further bees’ health, we need to foster a successful breeding program that bolsters a local stock best suited for our winters, as well as protects their genetic and microbial diversity. We can also preserve both urban and rural areas to save wild spaces for their genetic diversity and pollinator forage. In our own yards and city spaces we can plant more annuals, perennials, fruits, vegetables, herbs, trees, shrubs – and, yes, dandelions – and reduce or eliminate our dependence on pesticides.

In our economic system individuals can make wise decisions on what products to buy and companies to support; this includes lawn and garden products containing neonicotinoids.

We have co-evolved with bees for millennia to a point of co-dependency. Recognizing that means helping, not hurting, the hives that help us feed.

The Plight of the Bees

We have a trillion-member work force responsible for pollinating a third of our food supply – and they are dying at a record rate.

For years worldwide, an increasing number of hives have been found empty come spring. Unlike diseased hives, that are found each new year with dead bees around them (caused by parasites or pathogens), the complete disappearance of entire hives has puzzled scientists and apiarists.

The mystery of this mass exodus is not fully understood, but since 2006 this phenomenon has been termed Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD).

At stake, a massive chunk of our food system: nationwide crops pollinated by bees have been valued at around $15-20 billion, according to the Natural Resources Defense Council. Crops dependent largely on bee pollination include apples, cucumbers, blueberries and watermelons; the almond industry relies solely on bees.

Until now, environmentalists have pointed fingers at neonicotinoids, a form of insecticide produced by many large pesticide manufacturers, but have had insufficient evidence to support their claim. However, a study this May out of the Harvard School of Public Health supports the causal link between neonicotinoids in conjunction with cold temperatures in contributing to CCD.

Europe did not wait long to act. Last year the European Commission banned the use of neonicotinoids for two years in light of research showing their effect on honeybees, as well as other pollinating insects. In the U.S., New York, and Eugene, Oregon are the only state and city, respectively, that have banned neonicotinoids, according to news reports, while Minnesota’s Department of Agriculture has them under review. Wisconsin has not moved on the deepening crisis.

The core issue comes down to an industrial food system that has evolved over the past decades into one that is largely monoculture, requiring vast amounts of pesticides, which in turn cause manifold effects throughout the environment.

Human-driven bee migration from crop to crop (pollinating large industrial farms seasonally) leaves those hives to occupy “green deserts,” as Charlie Koenen calls them, because bees need nectar and pollen, not leaves and green oases.

The decreasing genetic diversity in plants, combined with large amounts of pesticides, has weakened the immune systems of crops and the animals that feed on them, including bees, leaving them vulnerable to disease and parasites, and requiring a constant cycle of antibiotic use.

Until the public gets involved, down to decisions each individual makes about food and the pesticides that went into it, bees will continue to suffer, say local bee advocates.

“We need to rethink our relationship with agriculture from the bottom up, because from the top down it is not going to change until it collapses,” Koenen said.

Do You Wannabee?

The first thing any beekeeper will tell you is that anyone can keep bees.

The second thing they’ll tell you is that you shouldn’t be scared.

Bees and beekeeping have their stigmas, but rest assured, there’s an abundance of knowledge, materials and skilled help available. You can become a beekeeper in no time.

The benefits of keeping bees are numerous. First, you’ll have a workforce to pollinate your garden. Second, after at least a year and a healthy hive – you’ll need to let your bees keep their honey the first year – you’ll get an abundant supply of honey. Finally, you’ll be contributing to the genetic diversity of the species, and helping the worldwide plight of the honeybee.

You’ll certainly need to check your local city ordinances. The City of Milwaukee passed one in 2010 allowing up to two honeybee hives on private property. The city requires a permit including approval of neighbors, sitemap, proof of beekeeping competency (UW Extensions, Beepods, and beekeeper associations all offer this), and a city inspection.

However, not all cities allow beekeeping. Wauwatosa, for one, is currently debating its outdated beekeeping ordinance, while the City of Cudahy doesn’t even allow it.

After obtaining your permit, some planning is needed to prepare for your “package” of one queen and two to three pounds of workers bees to arrive in the spring. Bees have an exact memory of their hive’s location, so you need to find a site for your hive to stay put.

There is an upfront cost for materials and starter packages of bees, running into the hundreds of dollars for a couple of hives. But cheaper hives can work fine.

The most common challenges for the beekeeper, according to local experts: exposure to pesticides, disease and, of course, weather.

However, it’s well worth the investment. With a happy, healthy hive you can live in a well-balanced, symbiotic relationship that is intimate, with deep historical roots.