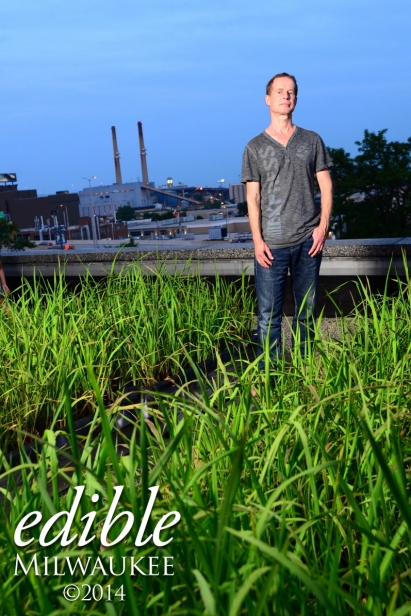

Rice on the Roof

Marquette scientist’s research goes global to restore local connections

Downtown Milwaukee’s urban foodscape just went global. Twelve rice paddies can be found on the roof of Marquette University and two at Alice’s Garden, where rice varieties from Uzbekistan to West Africa are being grown. Thanks to Marquette University Professor Michael Schläppi, the city is contributing to worldwide rice research—and reuniting ethnic groups with their ancestral grains.

The future holds a rice species adapted for Wisconsin and hopefully a new crop for the area.

There are roughly 40,000 rice varieties, or “races,” grown in all fertile continents. It’s an aquatic species that roots itself in the mud under shallow water. About 150 kernels grow per stem, yielding approximately 7,000 lbs. per acre. The colors, shapes and sizes of rice have a beautiful diversity that can be appreciated in part by visiting a bulk foods section, where you can see Japanese white sushi, Chinese green jade and African red rice.

At Marquette’s Biological Sciences Department, Dr. Schläppi has been successfully growing rice since 2010. In collaboration with the USDA, he has seed samples of roughly 200 rice varieties drawn from a cross-section of rice’s gene bank.

What has spurred Dr. Schläppi’s interest is how plant varieties of the same species adapt to different environments. What are the genes that allow for cold tolerance, where are they located, and how do they work? To answer these questions he is using traditional plant breeding and genetic mapping to find cold-tolerant genes in the rice chromosomes.

There are a handful of rice research labs domestically that study rice diversity and evolution, as opposed to productivity and genetic modification (which serve industrial food production). Dr. Schläppi’s lab, in collaboration with the Rice Research Center at the University of Arkansas, is currently the only one in the U.S. doing large-scale mapping of cold tolerant/sensitive genes.

Rice has its origin around the Yangtze and Pearl Rivers in China, but might have a second source in India. Nevertheless, experts generally agree that in Asia rice was cross-bred to be domesticated into today’s cultivated rice, Oryza sativa L. It is from these cradles that rice evolved into two main subspecies, Indica and Japonica. Indicais the more genetically diverse of the two, primarily grown in mainland Asia and Africa, while Japonica varieties are grown in the Americas, Europe, Japan and northern China, says Dr. Schläppi. From these cradles rice was carried around the world, being bred with local species for texture and taste yielding the different varieties we have today.

Though cultivated rice is not native to the U.S. or our main starch staple, it is grown commercially in six states. According to the U.S. Rice Federation, Arkansas produces nearly half of the nation’s 20 billion pounds per year, followed by California, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri and Texas—making up two percent of the world market.

Wisconsin does not have a native rice species; however, we do have wild rice, Zizania palustris, which is taxonomically a grass and only distantly related to rice. It yields long, slender, dark-brown kernels.

With roughly half the global population dependent on rice—consuming it as a primary staple—its production often means the difference between national security or insecurity. This helps motivate researchers around the world to study the evolution of rice as well as environmental stresses, diversity and yield. In China, where Dr. Schläppi has conducted research, the government mobilizes its academic sector in response to changing agricultural challenges.

Dr. Schläppi is examining more drastic shifts in the environment that inevitably stress plants. These conditions can arise from growing a species outside its ecological niche, like rice in Wisconsin, or from a major climate event like an ill-timed monsoon.

For Dr. Schläppi the mechanisms of adaptation are vital in this changing world. Stressors on a plant growing outside its niche can trigger an “adapt or die” response, he says. By stressing different varieties in the lab he can see if they have desired genes allowing it to adapt—and speed up a process that might otherwise take generations of cross-breeding.

This form of plant research is not genetic engineering (GE), but human selection that has been conducted since the beginnings of agriculture. Dr. Schläppi says GE could be used, however it is not necessary. Cross-breeding is inherently slow and poses a challenge, he says, but he nevertheless is finding success by mapping stress tolerance genes.

Though Dr. Schläppi’s main goal, to find a species tolerant enough to grow in Wisconsin, is still in progress, his findings thus far have been promising. Currently, he and his lab assistants have found several chromosomal regions and a few dozen cold tolerance genes they are narrowing down. He says he has discovered enough to publish, hopefully by year’s end. These results along with the first crop of Wisconsin-grown rice are currently his proudest scientific accomplishments.

The first application of this research has begun two miles north of Schläppi’s lab, in Alice’s Garden, a community garden and urban farm off North Avenue. There, he worked with Director Venice Williams, garden members, and a crew of local teenagers to construct two paddies this past June—an extension of the Garden’s pre-existing Fieldhands and Foodways Program speaking to African-American history.

African rice cultivation became known to Europeans as early as 1444 with the Portuguese arrival in Senegambia, on the West African coast, according to Judith Carney’s Black Rice: The African origins of rice cultivation in the Americas. This area became known as the Grain or Rice Coast, where millet, sorghum and rice were grown, providing some of the provisions for the Atlantic Slave Trade to America. In 1685 rice was brought to the South Carolina and Georgia coasts due to their similar climates and landscapes. Slavers appropriated West African peoples (often women), along with their seeds and rice-growing knowledge, to work on rice plantations until they were emancipated after the Civil War.

The two paddies are a catalyst for all who visit the garden to learn about a history that is ingrained, but often unknown, in our society and cuisines. The species of rice planted this year came from multiple West African countries, reuniting humans, plants and genes in urban Milwaukee.

The long-term goal, says Schläppi, is to grow rice from around the world to actively connect local ethnicities with their ancestral cereals, many of which have not been grown in thousands of years. This is a reunification that spans generations and leaps over history remembered and unknown.

To incorporate some of his own culture into the discussion, Dr. Schläppi brought a dish of risotto, made from arborio rice, from his native Switzerland, to a lecture in the garden. “Humans’ well-being, identity and culture is in part their connection to food,” he says. And with every step forward in his research, he helps revitalize a heritage of what was and what can be again.

Wild Rice: The Good Berry

Native to North America and primarily grown in the Upper Great Lakes region, this aquatic cereal has long been a staple to native peoples, including the Ojibwe and Menominee, who introduced the grain to the region’s first French explorers, who called it

“wild oats.”

Milwaukee’s inner harbor was once filled with wild rice, making it a regional food cache. The word for wild rice is manoomin, translated as the “good berry.” This may give insight into the meaning of Milwaukee being the “good land,” due to its waterborne bounty.

This cereal gave sustenance to a nation of people who hold a deep respect for its central role in their culture. In one vivid example, in the Treaty of 1854 during the U.S. Government’s western land scramble, the last plea of local native groups was to retain their right to hunt, fish and forage, including for manoominon the land they were forced to relinquish.

Wild rice grows on the edge of streams, rivers and lakes and has been harvested traditionally by way of canoe and flail (a short, round wooden stick)—still the method used by individual harvesters in Wisconsin.

Currently Wisconsin has 70 prominent wild rice fields in 13 different counties in the northern quarter of the state. In our area it is common to find Minnesota- or Canadian-grown wild rice; however, with enough determination and a pit stop at a corner gas station up North you can find some hand-harvested, wild-grown, Wisconsin wild rice.